2 Defining Random Variables

In the first week, you reasoned about the most fundamental elements of frequentist probability: a sample space that defined the total enumeration of all outcomes that are possible, an event space that is all the events possible within that sample space, and a set of rules that establish a valid probability statement.

Building upon this foundation, you learned to think about the probability that two events happened at the same time (joint probability), the probability that one event happens, provided that another has happened (conditional probability), and how to rearrange some of our basic building blocks to “derive” Bayes’ Rule.

These building blocks are very general. The events that we were thinking of could have been as diverse as acceptance into a graduate program, measuring a quark, probability of some utterance within a longer string of words – quite literally anything! On the one hand, this means that any property that we can prove in this very general case will have to be true in any particular case. But, on the other hand, it can feel pretty abstract.

This week, we’re going to introduce a new concept, the random variable which is nearly as abstract as the set theory probability from last week. These random variables are structures that we can use to hold events in the world. In this way, they’re quite similar to the sets from last week. New, this week, is that we’re going to have specific statements about the probability that some specific outcome occurs – this is the probability distribution (or density in the continuous case).

We are also going to provide some specific mathematical concepts that define the relationships between different views of the probability distribution.

2.1 Learning Objectives

At the end of this week’s course of study (which includes the async, sync, and homework) students should be able to

- Remember that random variable are neither random, or variables, but instead that they are objects thare are a foundation that we can use to reason about a world.

- Understand that the intuition developed by the use of set-theory probability maps into the more expressive space of random variables

- Apply the appropriate mathematical transformations to move between joint, marginal, and conditional distributions.

This week’s materials are theoretical tooling to build toward one of the first notable results of the course, conditional probability. This is the idea that, if we know that one event has occurred, we can make a conditional statement about the probability distribution for another, dependent distribution.

2.2 Introduction to the Materials

From the axioms of probability, it is possible to build a whole, expressive modeling system (that need not be grounded at all in the minutia of the world). With this probability model in place, we can describe how frequently events in the random variable will occur. When variable are dependent upon each other, we can utilize information that is encoded in this dependence in order to make predictions that are closer to the truth than predictions made without this information.

There is both a beauty and a tragedy when reasoning about random variables: we describe random variables using their joint density function.

- The beauty is that by reasoning with such general objects – the definitions that we create, and the theorems that we derive in this section of the course – produce guarantees that hold in every case, no matter the function that stands in for the joint density function. We will compute several examples of specific functions to provide a chance to reason about these objects and how they “work”.

- The tragedy is that in the “real world”, the world where we are going to eventually going to train and deploy our models, we are never provided with this joint density function. Because we don’t have access to the joint density function, in later weeks we will try to produce estimates using data. The simpler the estimate, the less data we need; the fuller the representation of the joint density function we desire, the more data we need.

Perhaps this is the creation myth for probability theory: in a perfect world, we can produce a perfect result. But, in the “fallen” world of data, we will only be able to produce approximations.

2.3 Class Announcements

Homework

- You should have turned in your first homework. The solution set for this homework is scheduled to be released to you in Thursday at 2:00p. The solution set contains a full explanation of how we solved the questions posed to you. You can expect that feedback for this homework will be released back to you within seven days.

- You can start working on your second homework when we are out of this class.

Study Groups

It is a very good idea for you to create a recurring time to work with a set of your classmates. Working together will help you solve questions more effectively, quickly, and will also help you to learn how to communicate what you do and do not understand about a problem to a group of collaborating data scientists. And, working together with a group will help you to find people who share data science interests with you.

Course Resources

There are several resources to support your learning. A learning object last week was that you would be introduced to each of these systems. Please continue to make sure that you have access to the:

- Library VPN to read all of the scholarly content in the known universe, including the course textbook.

- Course LMS Page

2.4 Using Definitions of Random Variables

2.4.1 Random Variable

What is a random variable? Does this definition help you?

A random variable is a function \(X : \Omega \rightarrow \mathbb{R},\) such that \(\forall r \in \mathbb{R}, \{\omega \in \Omega: X(\omega) \leq r\} \in S\).

Someone, please, read that without using a single “omega”, \(\mathbb{R}\), or other jargon terminology. Instead, someone read this aloud and tell us what each of the concepts mean.

You might notice that the \(X(\omega) \leq r\) feels kind of weird; why isn’t it just \(X(\omega) = r\)? After all, this is a mapping from an outcome, \(\omega \in \Omega\) to a real number, right? So, why not just be direct about it? The answer is a real deep-dive, and one that is better suited to a formal measure theory course.

The short (but deeply technical) answer, is that the we use this \(\leq r\) range because we’re using a Boreal \(\sigma\) algebra to constrain the sets that have probability measures. Why this constraint? If we don’t weird stuff can happen. Like, real weird things: you can split a sphere into pieces and create two new spheres of equal volume from the pieces (Banch-Tarski Paradox). This is an example of a formal language allowing scholars to examine really far out implications of the theory; but, it isn’t something that we’re going to engage in this course.

The goal of writing with math symbols like this is to be absolutely clear what concepts the author does and does not mean to invoke when they write a definition or a theorem. In a very real sense, this is a language that has specific meaning attached to specific symbols; there is a correspondence between the mathematical language and each of our home languages, but exactly what the relationship is needs to be defined into each student’s home language.

What are the key things that random variables allow you to accomplish?

Suppose that you were going to try to make a model that predicts the probability of winning “big money” on a slot machine. Big money might be that you get 🍒🍒🍒. Can you do math with 🍒?

Suppose that you wanted to build a chatbort that uses a language model so that you don’t have to do your homework anymore. How would you go about it? Can you do math on words or concepts?

Suppose you want to direct class support to students in 203, but their grades are scored

[A, A-, ..., C+]and features include prior statistics classes grades, also scoredA, A-, ..., C+].

2.5 Pieces of a Random Variable

There are two key pieces that must exist for every random variable. What are these pieces?

A random variable is a function \(X : \Omega \rightarrow \mathbb{R},\) such that \(\forall r \in \mathbb{R}, \{\omega \in \Omega\}: X(\omega) \leq r\} \in S\).

The new piece is provided to us in Definition 1.2.1 Random Variable (on page 16). The older piece (from last week) that is now useful is a part of the Kolmogorov Axiom, the probabilty triple: \((\Omega, S, P)\) where \(\Omega\) is a sample space, \(S\) is an event space, and \(P\) is a probability-measure.

Suppose that a random variable is simple and discrete. For concreteness, you could think of this random variable as the answer to the question, “Is the grass wet outside?”.

- What is the sample space?

- What is a sensible function that you might use to map from the sample space to real values? (A student well-seasoned in Maths might use (and define for the rest of the class) the concept of a bijective function).

- If you simply had the values that the random variable function maps to are you guaranteed to be able to describe the entire sample space? Why or why not?

- How would you go about determining the probability mass function for this random variable?

2.5.1 Functions of Functions

Why do we say that random variables are functions? Is there some useful property of these being functions rather than any other quantity? What else could they be if not a function?

What about a function of a random variable, which is a function of a function.

Let \(g : U \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) be some function, where \(X(\Omega) \subseteq U \subseteq \mathbb{R}\). Then, if \(g \circ X : \Omega \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) is a random variable, we say that \(g\) is a function of X and write \(g(X)\) to denote the random variable \(g \circ X\).

If a random variable is a function from the real world, or the sample space, or the outcome space to a real number, then what does it mean to define a function of a random variable?

- At what point does this function work? Does this function change the sample space that is possible to observe? Or, does this function change the real-number that each outcome points to?

Suppose that you are doing some image processing work. To keep things simple, that you are doing image classification in the style of the MNIST dataset.

- Can someone describe what this task is trying to accomplish?

- Has anyone done work like this?

However, suppose that rather than having good clean indicators for whether a pixel is on or off, instead you have weak indicators – there’s a lot of grey. A lot of the cells are marked in the range \(0.2 - 0.3\).

- How might creating a function that re-maps this grey into more extreme values help your model?

- Is it possible to “blur” events that are in the outcome space? Does this “blurring” meet the requirements of a function of a random variable, as provided above?

2.5.2 Probability Density Functions and Cumulative Distribution Functions

- What is a probability mass function?

- What do the Kolmogorov Axioms mean must be true about any probability mass function (pmf)?

You should try driving in Berkeley some time. It is a trip! Without being deliberately ageist, the city is full of ageing hippies driving beater Subaru Outbacks and making what seem to be stochastic right-or-left turns to buy incense, pottery, or just sourdough bread.

Suppose that you are walking to campus, and you have to cross 10 crosswalks, each of which are spaced a block apart. Further, suppose that as you get closer to campus, there are fewer aging hippies, and therefore, there is decreasing risk that you’re hit by a Subaru as you cross the street. Specifically, and fortunately for our math, the risk of being hit decreases linearly with each block that you cross.

Finally, campus provides you with the safety reports from last year, and reports that there were 55 student-Subaru incidents last year, out of 10,000 student-crosswalk crossings.

- What is the pmf for the probability that you are involved in a student-Subaru incident as you walk across these 10 blocks? What sample space, \(\Omega\) is appropriate to represent this scenario?

- How would you describe the cumulative probability of being hit as you walk closer to campus? That is, suppose that you start 10 blocks away from campus, and are walking to get closer. Is your cumulative probability of being hit on your way to campus increasing or decreasing as you get closer to campus?

- How would you describe the cumulative probability of being hit as you walk further from campus? That is, suppose that you start on campus, and you’re walking to a bar after classes. Is your cumulative probability of being hit on your way away from campus increasing or decreasing as you get further from campus?

- Suppose that you don’t leave your house – this is a remote program after all! What is your cumulative probability of being involved in a student-subaru incident?

- Suppose that you live three blocks from campus, what is the cumulative probability cmf for the probability that you are involved in a student-Subaru incident?

- Suppose that you live three blocks from campus, but your classmate lives five blocks from campus. What is the difference in the cumulative probability?

2.6 Discrete & Continuous Random Variables

What, if anything is fundamentally different between discrete and continuous random variables? As a way of starting the conversation, consider the following cases:

- Suppose \(X\) is a random variable that describes the time a student spends on w203 homework 1.

- If you have only granular measurement – i.e. the number of nights spent working on the homework – is this discrete or continuous?

- If you have the number of hours, is it discrete or continuous?

- If you have the number of seconds? Or milliseconds?

- Is it possible that \(P(X = a) = 0\) for every point \(a\)? For example, that \(P(X = 3600) = 0\).

- Does one of these measures have more information in it than another?

- How are measurement choices that we make as designers of information capture systems – i.e. the machine processes, human processes, or other processes that we are going to work with as data scientists – reflected in both the amount of information that is gathered, the type of information that is gathered, and the types of random variables that are manifest as a result?

2.7 Moving Between PDF and CDF

The book defines pmf and cmf first as a way of developing intuition and a way of reasoning about these concepts. It then moves to defining continuous density functions, which is many ways are easier to work with although they lack the means of reasoning about them intuitively. Continuous distributions are defined in the book, and more generally, in terms of the cdf, which is the cumulative distribution function. There are technical reasons for this choice of definition, some of which are signed in the footnotes on the page where the book presents it.

More importantly for this course, in Definition 1.2.15 the book defines the relationship between cdf and pdf in the following way:

For a continuous random variable \(X\) with CDF \(F\), the probability density function of \(X\) is

\[ f(x) = \left. \frac{d F(u)}{du} \right|_{u=x}, \forall x \in \mathbb{R}. \]

The implies, further, that for a random variable \(X\) with PDF \(f\), the cumulative density function of \(X\) is:

\[ F(x) = \int f(x) dx, \forall x \in \mathbb{R}. \]

- How does this definition, which relates pdf and cdf by a means of differentiation and integration, fit with the ideas that we just developed in the context of walking to and from campus?

Suppose that you learn than a particular random variable, \(X\) has the following function that describes its pdf, \(f_{x}(x) = \frac{1}{10}x\). Also, suppose that you know that the smallest value that is possible for this random variable to obtain is 0.

- What is the CDF of \(X\)?

- What is the maximum possible value that \(x\) can obtain? How did you develop this answer, using the Kolmogorov axioms of probability?

- What is the cumulative probability of an outcome up to 0.5?

- What is the probability of an outcome between 0.25 and 0.75? There are two ways to produce an answer to this in two ways:

- Using the \(PDF\)

- Using the \(CDF\)

2.8 Joint Density

Working with a single random variable helps to develop our understanding of how to relate the different features of a pdf and a cdf through differentiation and integration. However, there’s not really that much else that we can do; and, there is probably very little in our professional worlds that would look like a single random variable in isolation.

We really start to get to something useful when we consider joint density functions. Joint density functions describe the probability that both of two random variables. That is, if we are working with random variables \(X\) and \(Y\), then the joint density function provides a probability statement for \(P(X \cap Y)\).

In this course, we might typically write this joint density function as \(f_{X,Y}(x,y) = f(\cdot)\) where \(f(\cdot)\) is the actual function that represents the joint probability. The \(f(\cdot)\) means, essentially, “some function” where we just have not designated the specifics of the function; you might think of this as a generic function.

2.8.1 Example: Uniform Joint Density

Suppose that we know that two variables, \(X\) and \(Y\) are jointly uniformly distributed within the the support \(x \in [0,4], y \in [0,4]\). We have a requirement, imposed by the Kolmogorov Axioms that all probabilities must be non-zero, and that the total probability across the whole support must be one.

- Can you use these facts to determine answers to the following:

- What kind of shape does this joint pdf have?

- What is the specific function that describes this shape?

- If you draw this shape on three axes, and \(X\), and \(Y\), and a \(P(X,Y)\), what does this plot look like?

- How do you get from the joint density function, to a marginal density function for \(X\)?

- How do you get form the joint density function, to a marginal density function for \(Y\)?

- How do you get from these marginal density functions of \(X\) and \(Y\) back to the joint density? Is this always possible?

2.8.2 Examples: A Triangle Distribution

Suppose that for two random variables the joint density of the random variables unknown, but that it looks like the following:

2.8.3 Triangle Math

Write down the function that accords with the figure that you’re seeing above.1

- What is a full statement of the PDF of this image?

- What is the marginal distribution of \(X\), \(f_{X}(x)\)?

- What is the marginal distribution of \(Y\), \(f_{Y}(y)\)?

- Using the definition of independence, are \(X\) and \(Y\) independent of each other?

- What is the CDF of \(X\), \(F_{X}(x)\)?

2.8.4 Saddle Sores

Suppose that you know that two random variables, \(X\) and \(Y\) are jointly distributed with the following pdf:

\[ f_{X,Y}(x,y) = \begin{cases} a * (x^{2} - y^{2} + 1), & 0 < x < 1, 0 < y < 1 \\ 0, & \text{otherwise.} \end{cases} \]

saddle_sores <- function(x,y) {

prob = (x^2 - y^2 + 1)

}

x <- seq(from = 0, to = 1, by = 0.1)

y <- seq(from = 0, to = 1, by = 0.1)

z <- matrix(data = NA, nrow = length(x), ncol = length(y))

for(i in 1:length(x)) {

for(j in 1:length(y)){

z[j,i] <- saddle_sores(x[i], y[j])

}

}

plot_ly(x=~x, y=~y, z=~z) %>%

add_surface()This joint pdf is similar to the pdf that you can visualize above, under the distribution called “saddle”. The difference between this function and the image above is that the function bounds the with support of \(x\) and \(y\) on the range \([0,1]\). This is to make the math easier for us in the next step.

- Can you use these facts to determine the following?

- What value of \(a\) makes this a valid joint pdf?

- What is the marginal pdf of \(x\)? That is, what is \(f_{x}(x)\)?

- What is the conditional pdf of \(X\) given \(Y\)? That is, what is \(f_{x|y}(x,y)\)?

- Given these facts, would you say that \(X\) and \(Y\) are dependent or independent?

- If the support for this joint distribution were instead \([0,4]\) (rather than \([0,1]\)), how would the shape of the distribution change?

2.9 Computing Different Distributions.

2.9.1 Distribution 1

Suppose that random variables \(X\) and \(Y\) are jointly continuous, with joint density function given by,

\[ f(x,y) = \begin{cases} c, & 0 \leq x \leq 1, 0 \leq y \leq x \\ 0, & otherwise \end{cases} \]

where \(c\) is a constant.

- Draw a graph showing the region of the X-Y plane with positive probability density.

- What is the constant \(c\)?

- Compute the marginal density function for \(X\). (Be sure to write a complete expression)

- Compute the conditional density function for \(Y\), conditional on \(X=x\). (Be sure to specify for what values of \(x\) this is defined)

2.9.2 Distribution 2

Suppose that random variables \(X\) and \(Y\) are jointly continuous, with joint density function given by,

\[ f(x,y) = \begin{cases} 3xy(x+y) & 0 \leq \{x, y\} \leq 1 \\ 0 & otherwise \end{cases} \]

- Draw a graph showing the region of the X-Y plane with positive probability density. (Or, describe the shape if you can’t draw it.)

- Compute the marginal density function for \(X\). (Be sure to write a complete expression.)

- Compute the marginal density function for \(Y\). (Be sure to write a complete experession.)

- Compute the conditional density function for \(Y\), conditional on \(X\). (Be sure to specify for what values of \(x\) this is defined)

2.10 Conditional Probability

Conditional probability is incredible. In fact, without exaggeration, almost all of data science is an exercise in making statements about conditional probability distributions. Don’t believe us?

- What is the goal of a “customer churn” model or a conversion model?

- What is the goal of a language-completion model?

- What is the goal of flight-departures model?

If we possessed the whole information about a process; if we had the CDF that governed probability of occurrences, what kinds of statements would we be able to make? Would we even need data?

Using the distribution above, produce a statement of conditional probability, \(f_{Y|X}(y|x)\).

2.11 Visualizing Distributions Via Simulation

To this point in the course, we have focused on concepts in “the population” with no reference to samples. This is on purpose! We want to develop the theory that defines the best possible predictor if we knew everything (if we know formula of the function that maps from \(\omega \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\), and we know the probability of each \(\omega \in \Omega\) then we know everything). Beginning in week 5 of the course, we will talk about “approximating” (which we will call estimating) this best possible predictor with a limited sample of data.

However, at this point, to help build your working understanding, or intuition, for what is happening, we are going to work on a way to simulate draws from a population. In some places, people might refer to these as Monte Carlo methods – this is because the method was developed by von Neumann & Ulam during World War II, and they needed a way to talk about it using a code name. They chose Monte Carlo after a famous casino in Monaco.

2.11.1 Example: The Uniform Distribution

You: “Gosh. There sure are a lot of examples that use the uniform distribution. That must be a really important statistical distribution.”

Instructor: “Nah. Not really. We’re just using the uniform a bunch so that we don’t get too lost in doing math while we’re working with these concepts.”

We’ll start with a simple uniform distribution, but then we’ll make it a little more complex in a moment.

We can use R to simulate draws from a probability distribution function by providing it with the name of the distribution that we’re considering, the support of that distribution, or other features of the distribution. In the case of the uniform, the entire distribution is can be described just from it support.

So, suppose that you had a uniform distribution that had positive probability on the range \([1.1, 4.3]\). Why these? No particular reason. That is, suppose

\[ f_{X}(x) = \begin{cases} a & 1.1 \leq x \leq 4.3 \\ 0 & otherwise \end{cases} \]

What does this distribution “look like”? Because it is a uniform, you might have a sense that it will be a horizontal line. But, what is the height of that line? Aha! We could do the math to figure it out, or we could generate an approximation using a simulation.

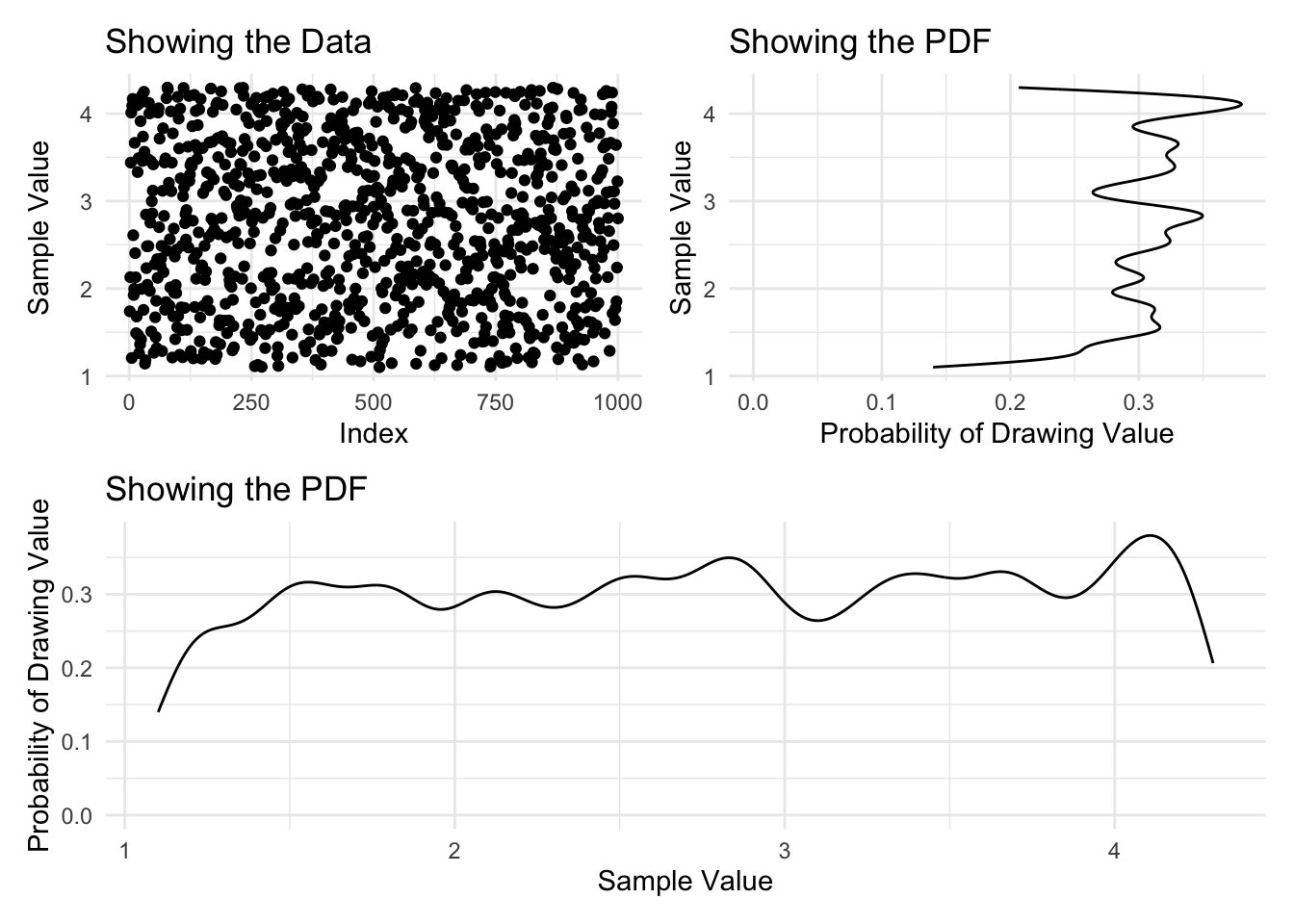

In the code below, we are going to create an object called samples_uniform that stores the results of the runif function call.

samples_uniform <- runif(n=1000, min=1.1, max=4.3)What is happening inside runif?

When you’re writing you own code, you can pull up the documentation for this (and any) function using a question mark, i.e. ?, followed by the function name – ?runif.

But, we can speed this up slightly by simply telling you that n is the number of samples to take from the population; min is the low-end of the support, and max is the high-end of the support.

If we look into this object, we can see the results of the function call. Below, we will show the first \(20\) elements of the samples_uniform object.

samples_uniform[1:20] [1] 3.189057 4.298127 3.463350 4.184894 1.290130 1.297939 3.621612 2.279325

[9] 4.158195 4.023943 2.832088 3.486832 1.289156 3.230349 2.280436 1.680590

[17] 3.859709 2.307495 3.404849 2.987571(Notice that R is a \(1\) index language (python is a zero-index language).)

With this object created, we can plot a density of the data and then learn from this histogram what the pdf looks like.

plot_full_data <- ggplot() +

aes(x = 1:length(samples_uniform), y = samples_uniform) +

geom_point() +

labs(

title = 'Showing the Data',

y = 'Sample Value',

x = 'Index')

plot_density <- ggplot() +

aes(x = samples_uniform) +

geom_density(bw = 0.1) +

labs(

title = 'Showing the PDF',

y = 'Probability of Drawing Value',

x = 'Sample Value')

(plot_full_data | (plot_density + coord_flip())) /

plot_density +

plot_layout(guides = "keep")

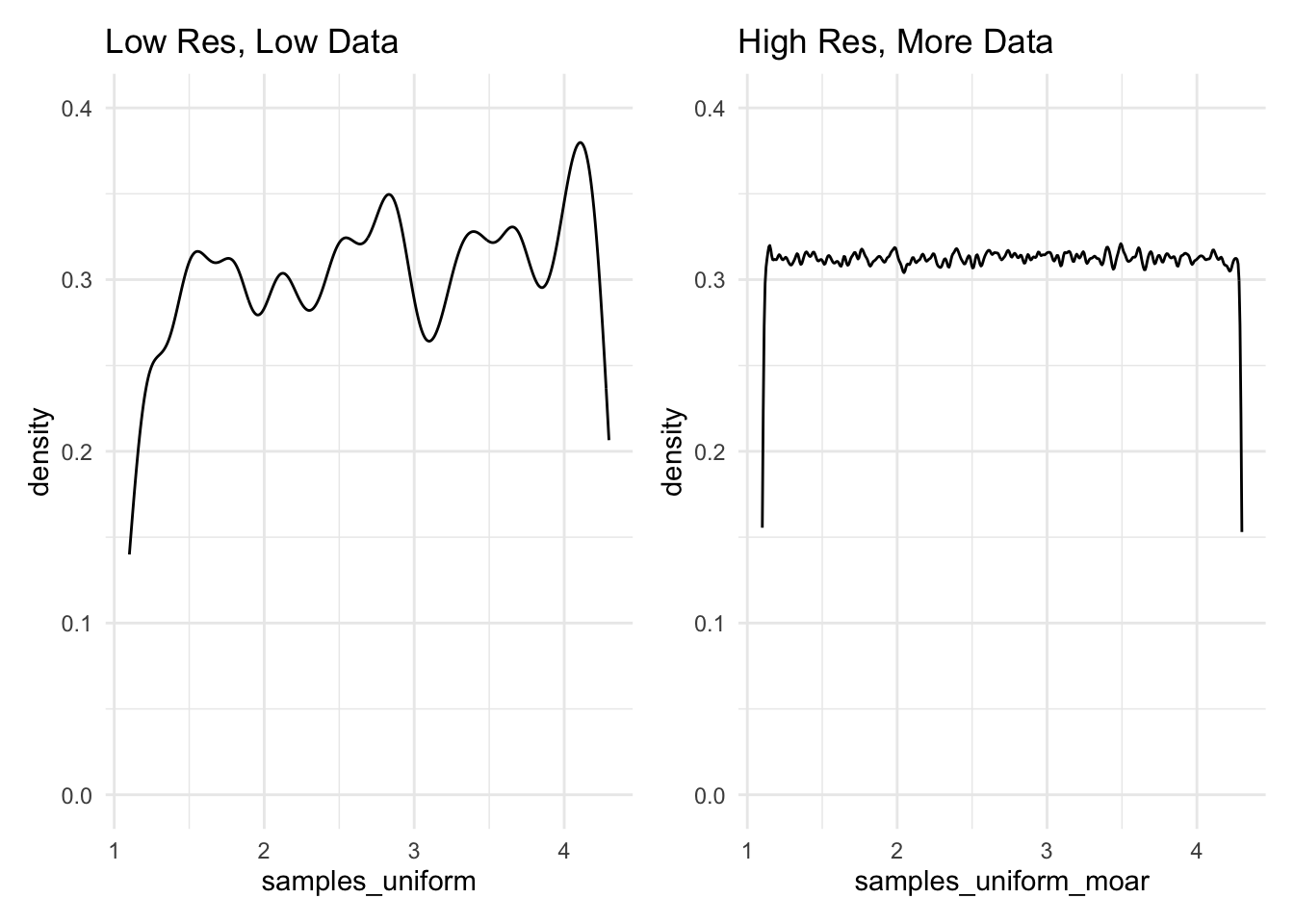

Interesting. From what we can see here, there does not appear to be any discernible pattern. This leaves us with two options: either, we might reduce the resolution that we’re using to view this pattern, or we might take more samples and hold the resolution constant. Below, two different plots show these differing approaches, and are very explicit about the code that creates them.

samples_uniform_moar <- runif(n = 1000000, min = 1.1, max = 4.3)plot_low_res <- ggplot() +

aes(x = samples_uniform) +

geom_density(bw = 0.1, from = 1.1, to = 4.3) +

lims(y = c(0,0.4)) +

labs(title = 'Low Res, Low Data')Warning in geom_density(bw = 0.1, from = 1.1, to = 4.3): Ignoring unknown

parameters: `from` and `to`plot_high_res <- ggplot() +

aes(x = samples_uniform_moar) +

geom_density(bw = 0.01, , from = 1.1, to = 4.3) +

lims(y = c(0,0.4)) +

labs(title = 'High Res, More Data')Warning in geom_density(bw = 0.01, , from = 1.1, to = 4.3): Ignoring unknown

parameters: `from` and `to`plot_low_res | plot_high_res

2.11.2 Example: The Normal Distribution

Folks might have some prior beliefs about the Normal distribution. Don’t worry, we’ll cover this later in the course. But, this is the distribution that you have in mind when you’re thinking of a “bell curve”.

We can use the same method to visualize a normal distribution as we did for a uniform distribution. In this case, we would issue the call rnorm, together with the population parameters that define the population. At this point in the course, we do not expect that you will know these (and, actually memorizing these facts are not a core focus of the course), but you can look them up if you like. Truthfully, statistics wikipedia is very good.

Do do you notice anything about the runif and the rnorm calls that we have identified? Both seem to name the distribution: \(unif \approx uniform\) and \(norm \approx normal\), but prepened with a r? This is for “random draw”.

Base R is loaded with a pile of basic statistics distributions, which you can look into using ?distributions.

samples_normal <- rnorm(n = 100000, mean = 18, sd = 4)Like before, we could look at the first \(20\) of these samples.

samples_normal[1:20] [1] 16.74574 15.02620 16.62681 16.32647 14.84687 19.48479 18.28910 13.67213

[9] 12.45297 16.82117 19.20076 20.14115 14.88331 20.13876 17.39272 19.11881

[17] 11.47461 27.81865 18.70895 17.74263And, from here we could visualize this distribution.

ggplot() +

aes(x = samples_normal) +

geom_density() +

labs(title = 'Visualization of this Normal Distribution')

2.11.2.1 Combining This Ability

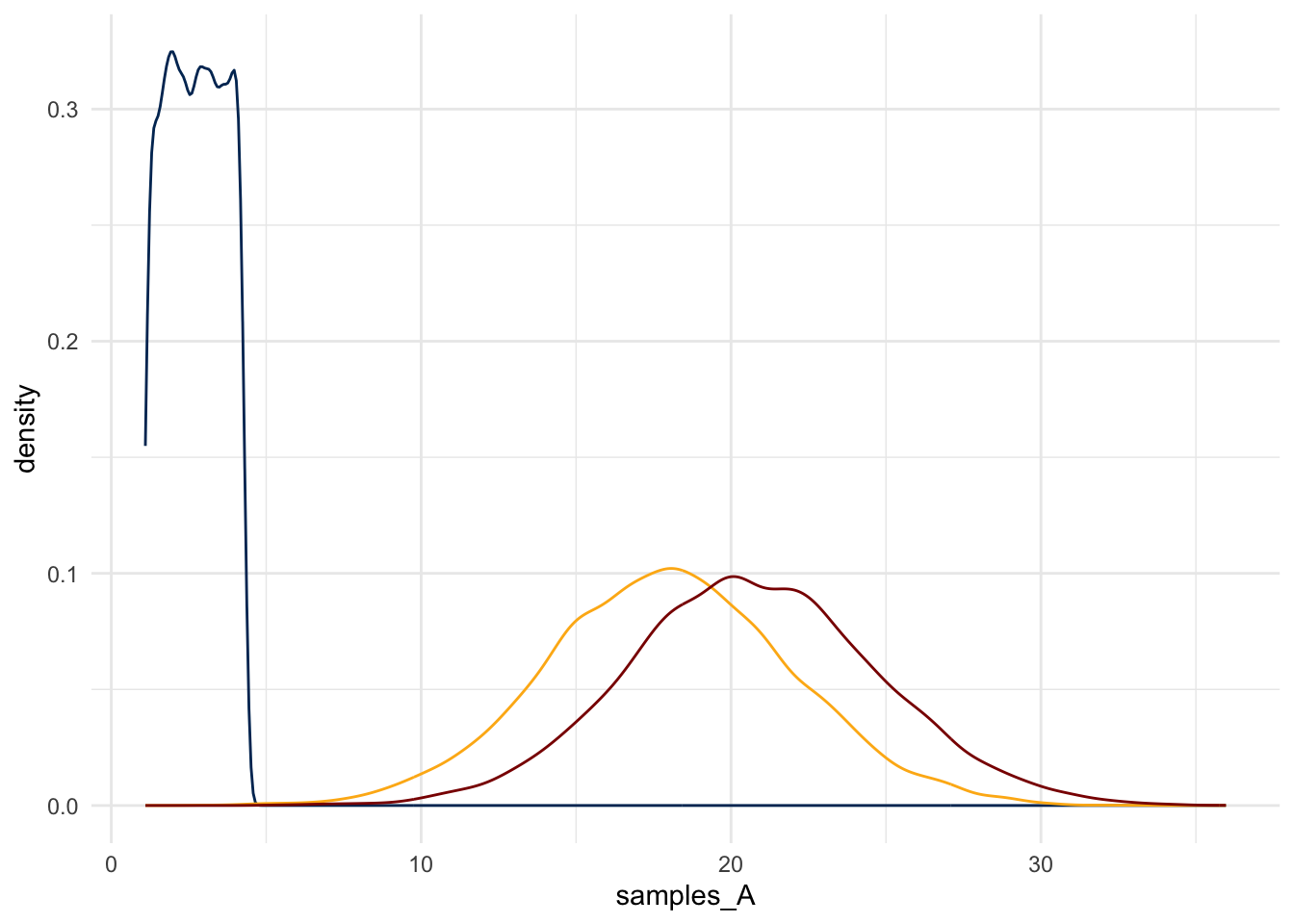

Consider three random variables \(A, B, C\). Suppose,

\[ \begin{aligned} A & \sim Uniform(min=1.1, max=4.3) \\ B & \sim Normal(mean=18, sd=4) \\ C &= A + B \end{aligned} \]

And, suppose that \(B\) is a random variable that is described by the normal density that we considered earlier. Suppose that \(A\) and \(B\) are independent of each other.

Finally, suppose that \(C = A + 2B\).

What does \(C\) look like?

Although this is a simple function applied to a random variable – a legal move – the math would be tedious. What if, instead, one used this simulation method to get a sense for the distribution?

samples_A <- runif(n = 10000, min = 1.1, max = 4.3)

samples_B <- rnorm(n = 10000, mean = 18, sd = 4)

samples_C <- samples_A + samples_Bplot_C <- ggplot() +

aes(x = samples_C) +

geom_density()

plot_C_and_A_and_B <- ggplot() +

geom_density(aes(x = samples_A), color = '#003262') +

geom_density(aes(x = samples_B), color = '#FDB515') +

geom_density(aes(x = samples_C), color = 'darkred')

plot_C_and_A_and_B

2.12 Review of Terms

Remember some of the key terms we learned in the async:

- Joint Density Function

- Conditional Distribution

- Marginal Distribution

Notice, that in general, this kind of curve fitting isn’t really a common data science task. Instead, this is just a learning task that lets the class assess their understanding of the definitions of random variables.↩︎